Or, What Biden’s pardoning of Hunter augurs for late-stage liberalism — and what we can learn about it from Poland

Here at The Blind Spot we’ve long highlighted that the “you’re either in power or in prison” dynamic, while largely alien to postwar Western states, is and always has been a feature of weak political systems where consensus over core political ideology is lacking.

The phenomenon most commonly emerges whenever political opponents view each other not as rivals within a shared framework of rules but as existential threats to be neutralized at all costs. From post-colonial power struggles in Africa to the shifting sands of Eastern Europe after the fall of communism, this zero-sum mindset has, through the ages, driven endless cycles of retribution and consolidation.

Leaders in such systems, fearing not just electoral loss but personal ruin, entrench themselves through purges, pardons, or both. The consequences are rarely stability-inducing.

And yet, none of this is uncommon in the grand scheme of history.

What is far more surprising, perhaps, is that over the course of the past century, so many post-war developed democracies have successfully managed to keep such forces at bay, maintaining in the process the construct of a “loyal opposition”.

Much of that resistance can be attributed to the uniquely extensive nature of the liberal consensus among Western populations and the respective trust it has cultivated in liberal institutions. This, in turn, has helped to solidify the efficiency of the core democratic structure, engendering even more trust.

But now that positive reinforcement dynamic has broken down.

In many cases, the positive feedback loop hasn’t just stopped reinforcing itself, it has morphed into a vicious cycle of tit-for-tat retaliation, leading to an even broader breakdown in institutional trust.

The first hint of the evolution came when political battles started moving from the ballot box to the courtroom. Then, when judicial processes began to fail, an even deeper truth was revealed: without robust systems of accountability and reconciliation, politics devolves into a desperate fight for survival where all the usual polite protocols suddenly go out the window.

The unsettling reality facing Westerners today is that institutional trust has now eroded so profoundly that the negotiate or purge cycle has become a norm that risks unsticking the exceptionalism of the post-war liberal consensus.

This is not a hypothetical or a one-off. Many sovereign nations have been through similar shifts, among them late-stage-communist Poland.

It’s not an unknown story, but far too many of the younger generation, even in Poland itself, are unaware of the unresolved grievances at its heart. The go-to post-communist narrative has too often conveniently forgotten essential parts of the story.

It’s a story worth retelling today because of the important insights it offers into the pros and cons of elites escaping justice on a systemic basis.

Lessons from Poland

Poland in the 1980s. A time when the Communist Party presided over a regime so hollowed out that its façade of legitimacy barely concealed its decayed interior. Officially a “government of unity”, Poland functioned under a de facto one-party state. Voters had no meaningful options, as every election merely reaffirmed the same ideological framework. Since political participation brought little change, it unsurprisingly dwindled.

Sound familiar?

We think so. The disillusionment of the era mirrors very closely the disillusionment being experienced by populations in late-stage liberal democracies today, where entrenched elites offer only variations on a theme, and more commonly than not foster detachment and frustration among the electorate.

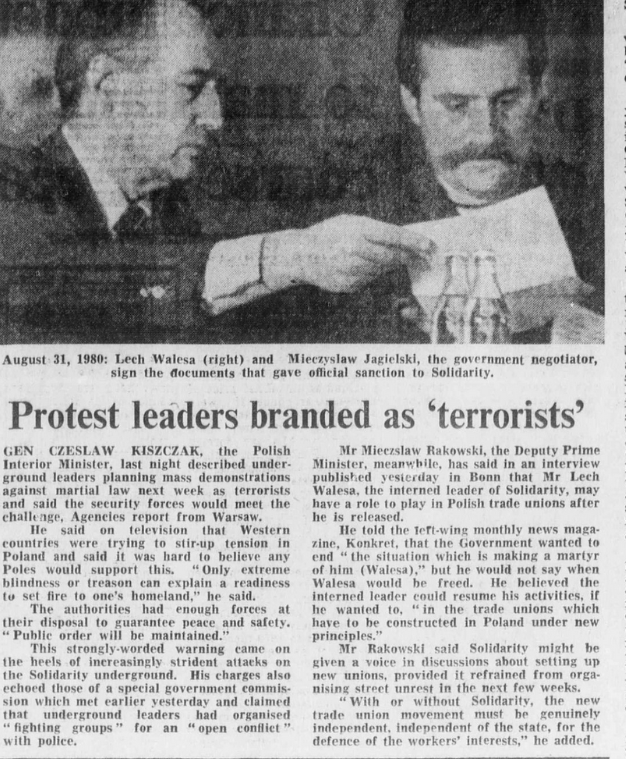

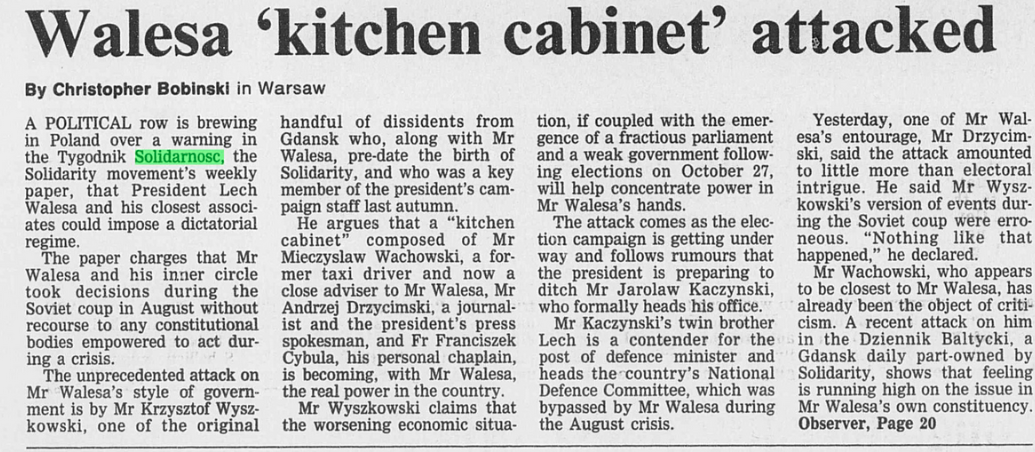

In Poland, the repression of genuine opposition eventually bred outsider movements. Solidarity, the trade union-cum-political force, surged in popularity. But even as it grew more powerful it was relentlessly demonized by the ruling elite, who soon became known as the nomenklatura. The result saw Solidarity labeled as radical, dangerous, and — crucially — manipulated by foreign interests.

Domestic propaganda on many occasions even accused Solidarity of having abject authoritarian objectives.

Whether they are communists, fascists or liberals, the above suggests the establishment’s playbook rarely changes much. Dismissal, smearing and demonization — not to mention accusations of dictatorial agendas — remain common tools for sidelining disruptive voices, whether they emerge from within a communist state or a liberal democracy. It’s the same playbook as always.

The pitfalls of a negotiated settlement

By 1989, the communist regime in Poland was facing a reckoning. Decades of economic mismanagement, authoritarian overreach, and rampant corruption had discredited the government entirely. The specter of revolution loomed. But instead of waiting for the guillotine, Poland’s elites opted for a roundtable parlay: a negotiated settlement with Solidarity.

These negotiations with key Solidarity figures birthed a new democratic framework. But the deal arrived at also, very importantly, included a de facto unspoken promise: that for the sake of the stability and cohesion of the country, a policy of mutual amnesty between all would be entertained.

As part of that deal, Solidarity’s political prisoners would be freed, while certain members of the communist order would be allowed to retain power. Crucially, most of the communist regime would be spared the full weight of justice. That meant no sweeping purges, no trials, no dismantling of entrenched networks.

The arrangement paved the way for the moderates among the communists to entirely reinvent themselves. By the mid-1990s, many had regained significant political power, with many high-profile members of the old communist Polish United Workers’ Party rising to top political positions.

For many Poles, however, this leniency felt like a betrayal. They contended the deal allowed the old power structures to morph into crony-capitalist networks.

When the right-wing PiS (Law and Justice Party) rose to power in 2005, it had become clear that the deal of 1989 had left too much unfinished business on the table. PiS had been forged out of an offshoot of the conservative factions of Solidarity. These elements strongly opposed the rapid privatization being promoted by moderates because of fears the process could be corrupted thanks to the weakness of Polish institutions. They also resented the sale of so many Polish state assets to foreign owners, which they viewed with suspicion.

This time, the party responded decisively. Efforts to expose alleged collaborators with the communist regime would be increased, with lustration presented as essential to Poland’s democratic consolidation.

Lustration nation

The lustration drive that began required public officials, academics, and journalists to declare whether they had ever collaborated with communist-era security services.

Separately, The Institute of National Remembrance, a guardian of the communist-era files, became central to the process. This is a notable point to emphasize because the Institute’s former director, Karol Nawrocki, has just been named by PiS as their prospective candidate for the upcoming 2025 presidential election.

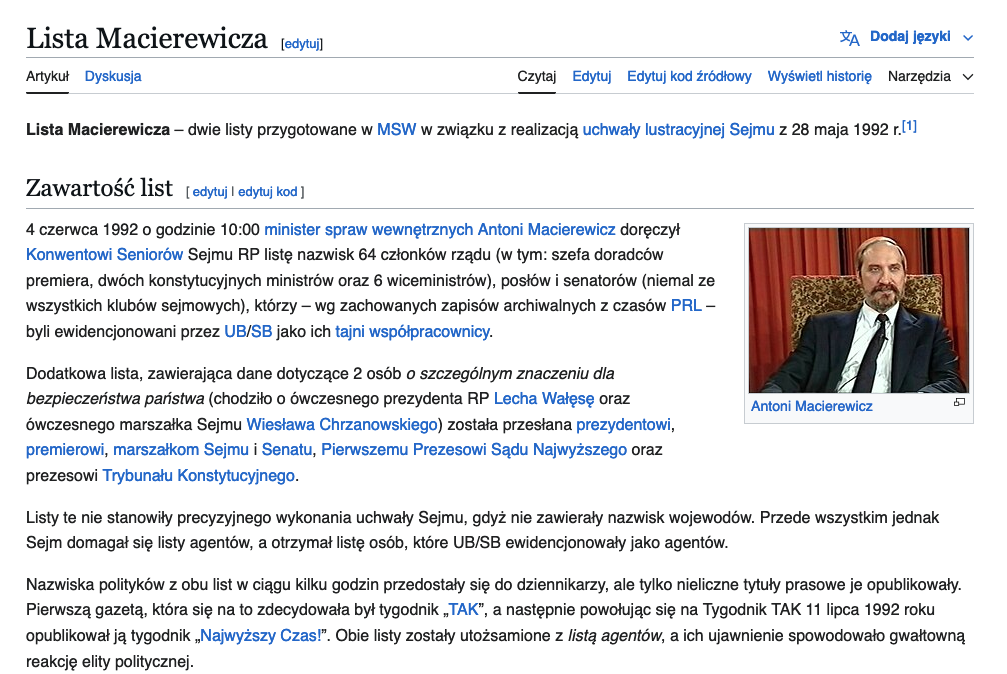

Within the Institute’s arsenal was something very controversial called the “Macierewicz List” (the Jeffrey Epstein list of its day). The document was compiled by Antoni Macierewicz, who was at the time Minister of Internal Affairs in Poland’s first post-communist administration under Prime Minister Jan Olszewski. As can be expected, the list drew extensively on the archives of the communist-era Ministry of Internal Security (SB) and its predecessors.

When the first version of the list was presented to the Polish Parliament (Sejm) on June 4, 1992, it sent the entire country into a tailspin. The document identified 64 individuals — among them government members, parliamentarians, and senators — all of whom had allegedly collaborated with the communist-era security services.

The most shocking name to be included on the list was that of Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarity movement himself. The list alleged he had operated as an asset or informant codenamed ‘Bolek’ for Poland’s equivalent of the KGB.

To say the consequences of the list’s publication were explosive would be an understatement.

The revelations stoked shock, paranoia, and defensiveness among the old guard who were outraged that their long-time opponents had dared to backtrack on the original amnesty agreement. They accused the former Solidarity men of inciting needless division and polarization.

The list had punctured the fragile pretense that grievances had been laid to rest. And no one was seemingly above suspicion — not even communism’s most famous resistance members. Nor did it help that the list was presented during a late-night session without prior warning.

Critics further claimed that many of the allegations could not be adequately verified or substantiated. SB records were too often incomplete, manipulated, or unreliable, due to having been produced by a regime that operated with secrecy and coercion. Others argued that many individuals were only listed because they had been forced to collaborate under duress.

The surrounding scandal eventually cost Olszewski his government.

Despite the pushback, just being named on the list proved damaging in a lasting way. Wałęsa’s inclusion especially opened people’s minds to how the regime may have manipulated the population by infiltrating opposition groups specifically to sabotage or control them from the inside. Wałęsa’s reputation never fully recovered from the incident.

From then on the list would prove a political wrangling point, coming in and out of focus as power flowed from the Solidarity hardliners to the parties of former Communist moderates and the emergent Civic Platform (PO) party of Donald Tusk.

While the latter lacked any prominent former Solidarity members, it nonetheless styled itself as having emerged from the anti-establishment elites and intelligentsia, and being cut from a very different cloth could rise above this cycle.

Party of reunification

When Civic Platform gained control from PiS in 2007 it once again sought to heal the divide and prioritize reconciliation. This saw the party move to scale down the previous administration’s lustration and purging agenda. As a result, a more cautious, less politically charged approach emerged.

But PiS thought PO were being naive. They argued the new policy meant individuals with ties to the communist-era security services were now being allowed to openly maintain powerful positions or infiltrate core systems, hindering Poland’s democratic consolidation and capacity to escape corruption.

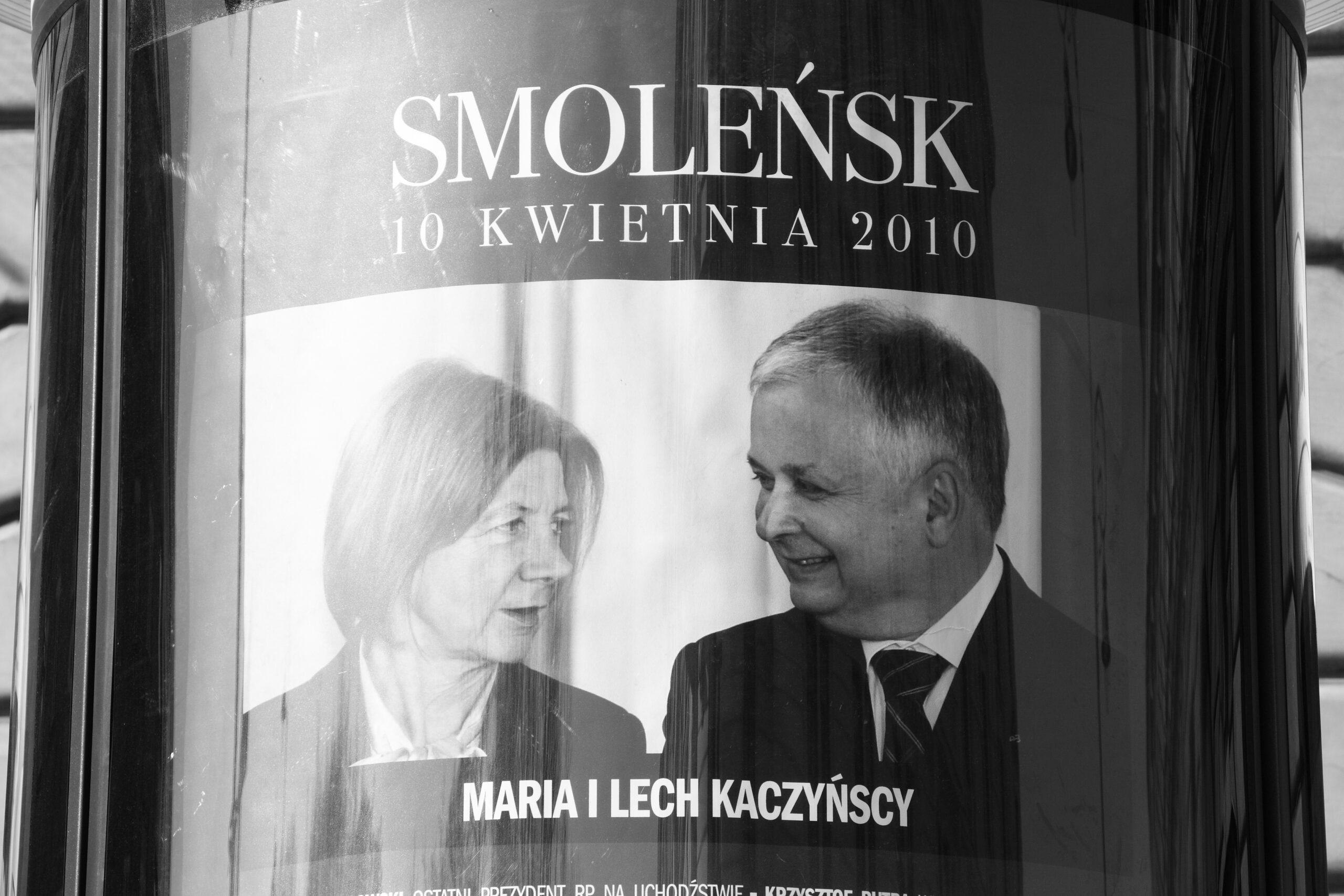

Just as the tussle was playing out in 2010, a Polish government plane carrying President Lech Kaczyński, the twin brother of PiS leader Jarosław, and 95 other major dignitaries crashed near Smolensk in Russia during heavy fog. The victims had been traveling to Smolensk to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Katyn Massacre, where thousands of Polish officers had been executed by Soviet forces during World War II in 1940, a fact Russia had only recently admitted to. There were no survivors from the crash.

Suspicions this was no mere accident immediately proliferated.

Before long, Antoni Macierewicz, the compiler of the original purge list — now also a prominent member of the PiS party — officially advanced claims that the Smolensk crash had not been an accident but an assassination orchestrated by Russia. Poland’s remnant secret services, he added, may also have been involved. Under Macierewicz’s watchful eye, the government initiated an official commission to investigate the accident, but — at least if you believe PiS claims — the probe was continuously obstructed by both Russian and domestic opposition forces.

The related intrigue, speculation, and mourning eventually paved the way for PiS’ return to power in 2015.

Public grievances against Civic Platform by this time had also been building up. The key complaints will be familiar to the anglosphere. Ordinary poles, especially those in rural areas, smaller towns, and lower-income groups, felt they had been left behind by the party’s key economic record. Inequality, cronyism and social alienation were rife. There was also a sense that PO had prioritized urban elites and EU interests over the struggles of everyday citizens.

Once back in power, PiS decided this time they would hold no prisoners. They immediately doubled down on their former purging agenda: judicial reforms, lustration lists, and an aggressive effort to root out anyone tied to the communist apparatus followed. The party members justified the actions as long-overdue justice, even as their opponents called it an authoritarian overreach.

Both sides argued with conviction, but the root problem was the same: the compromises of the past still haunted the present.

EU intervention

However, it was when the European Union deemed PiS’ judicial reforms an undemocratic attack on the independence of Polish Courts, that the negative feedback loop arguably began to spiral out of control. While PiS claimed the reforms were necessary to purge former SB-aligned parties from the judiciary, the EU’s much weightier voice convinced the world that PiS were acting like tinpot dictators.

The clash would be costly for the administration, both in terms of reputation and funding. Brussels moved to economically penalize Poland for its alleged “democratic backsliding” by withholding €137 billion of critical Covid recovery and cohesion funds unless key judges were reinstated.

In reality, however, EU leaders — who had never penalized Italy for similar contraventions — were engaging in their own revenge agenda. Among their biggest grievances was that the PiS government had defied the EU’s migration and LGBT policies. Poland had explicitly refused to take their share of EU refugee quotas in 2016 and onwards or to accept Commission directives normalizing LGBT+ rights. Equally troubling in the Commission’s mind was PiS’ control of the airwaves, specifically state media, which Brussels claimed meant independent media had been interfered with.

Forced into a defensive, PiS dug its heels in. They claimed the EU response was only to be expected since the institution had itself fallen under the influence of former communist apparatchiks. Any leaning on the media by them, meanwhile, was merely to correct for the bias of the largely foreign-owned independent press.

Since the Macierewicz list had failed to decisively prove communist linkages, the party became obsessed with finding other ways to expose remnant communist infiltration of the system. To do so they turned to somewhat unscrupulous tactics: Spying on the opposition with Israeli Pegasus software.

By 2023 the extent of the the surveillance operation directed by the PiS government became known. The public were horrified. They saw it as a betrayal of the very things key PiS figures had fought against in the 1980s.

Tusk expertly exploited the momentum for his own political ends.

The same year, running on a platform of vengeance against the authoritarians of the previous administration, Tusk returned to power as head of a new coalition government. But again, the angry rhetoric only intensified the retaliation cycle. Tusk — seemingly unable to stop himself from becoming everything he too had previously criticized — unironically began to turn to authoritarian tactics himself. His lustration drive, however, was not focused on purging former communists from the system but rather former PiS “authoritarians”.

The most recent example of the tit-for-tat race to the bottom going on in Warsaw is the hauling into Parliament this week of central bank board member and former PiS spy chief Piotr Pogonowski. He now faces a special commission looking into whether the former PiS-led government misused Pegasus hacking software to spy on its political opponents.

America at its roundtable

But now it’s time to turn back to the United States. The scandals surrounding Hunter Biden, though incomparable in scale to Poland’s communist collapse, pose a similar question about the durability of American institutions. The Hunter saga is not merely about personal misconduct but also a proxy for accusations of corruption and impropriety within the political elite. It underscores a growing perception that the system protects its own while punishing dissent.

The pardoning thus marks a watershed moment — a negotiated settlement of sorts. Indeed, Biden’s defenders are already framing it as a necessary act to prevent the descent into partisan revenge politics, and the only way to unify the country by protecting the former establishment from reprisal attacks.

But Trump supporters can also argue the pardon entrenches the very double standards fueling public disillusionment.

In the months to come, both sides will likely claim the moral high ground. And yet, the underlying choice mirrors that of Poland in 1989: amnesty or purge?

The ‘power or prison’ cycle

In conclusion, the Polish experience offers a cautionary tale. Amnesties may defuse immediate tensions but in exchange they leave grievances to fester. A purge, meanwhile, risks backlash, polarization, and instability — even potentially civil war. The final norm that emerges is often the same: you’re either in power or in prison.

Poland’s PiS government justified its own authoritarian tendencies as necessary to correct for the sins of the past. But in doing so, it mirrored the very behaviors it sought to condemn — spying on opponents, packing courts, and eroding institutional trust.

If Biden’s team views pardons as a way to stabilize the system, they too may be in for an uncomfortable surprise over the long term. History tells us negotiated settlements are rarely a resolution but a truce. If the protections derive from a legal loophole provided to both sides, rather than encouraging consolidation and healing, the utilization of that loophole may even do the opposite.

We predict that in Poland and America alike (if not further afield too), political morality will in the end take a backseat to economic performance in determining which path the warring parties ultimately take.

If that’s the case, PiS may just have the edge over PO in Poland since even the opposition has a tough time pretending that its populist economic policies did not revitalize Poland.

In the U.S., the Biden administration’s calculus will similarly rest on whether voters feel secure and prosperous, and if Trumpian policies flourish or fail. If, in the grand scheme of things, Bidenomics proves a greater success than Trumpism, the current pardon might just end up a footnote in a grander narrative of economic renewal upended. If Trumpism outperforms, however, you can expect the lustration drive to accelerate.

For now, the parallels are clear: whether in Warsaw in 1989 or Washington in 2024, the dilemma facing everyone is the same. Is it better to negotiate or purge? The answer is rarely never simple.

Related links:

Episode 14: You’re either in power or in prison — Blind Spot Podcast (April, 2023)

A wind of change at the National Bank of Poland — Blind Spot Newsletter (December, 2023)

M&A pipeline, Cbank funding models and Poland latest — Spot Markets Live (October, 2023)

Fintech, Miss Ukraine, Davos — Blind Spot Newsletter (January, 2023)

Black Ops Capital, Daisy Chain QE, Substack — Blind Spot Newsletter (April, 2023)