By Izabella Kaminska, July 10, 2023

PRAGUE/LONDON — Thanks to Elon Musk and the rise of Tesla Motors, the accomplishments of Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla, born July 10 — whose discoveries in the field of electromagnetic engineering and physics had, for most of the 20th century, been mostly overshadowed by those of his contemporary Thomas Edison — are, once again, front of mind everywhere around the world.

But this was far from the case in 1943. The inventor, best known for harnessing the power of electricity, passed away at the age of 86, alone and reportedly penniless in a room he had rented at the Hotel New Yorker in Manhattan. Anything of intellectual value left among his belongings — papers, diaries etc — was seized somewhat sharply by the Office of Alien Property. These items, contrary to FBI claims for decades, were later digested and analysed by specialist U.S. authorities for possible military or defence applications — a fact only confirmed in 2018 when another 64 pages of material pertaining to Tesla were declassified.

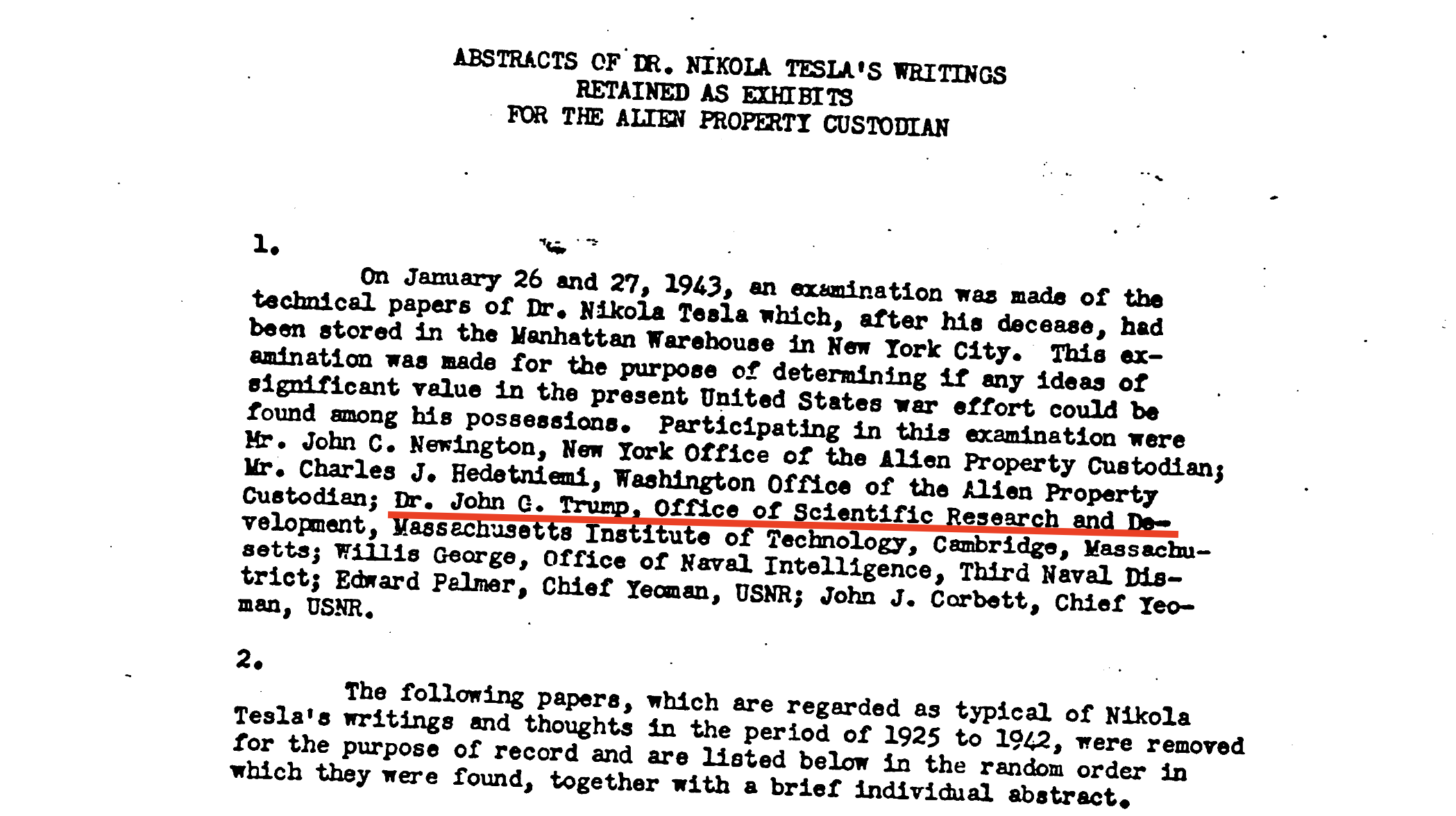

An unexpected twist to the tale is that among those brought in to analyse Tesla’s possessions was a certain John G. Trump, the paternal uncle of Donald J. Trump, who, at the time, identified himself as a technical aide within Division 14 of NIRC for the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) at MIT.

Trump’s surprising conclusion was that, while the work left over by Tesla hinted at new ways of transmitting power in a wireless way, it “did not include new sound, workable principles or methods for realising such results”. The heirlooms were a dud.

But the OSRD itself was no ordinary outfit. The US government had set it up to “coordinate scientific research for military purposes” in its war effort against Nazi Germany during WW2. What’s more, it had specifically been set up to be a non-military organisation, headed instead by private sector entities, notably Vannevar Bush, a highly regarded scientist, who was also the founder of the Raytheon company. Bush reported only to President Franklin Roosevelt throughout the appointment, and it was under his watch that the OSDR’s most notable and secret projects, such as the Manhattan Project, came to life.

Trump, for his part, went on to become a prominent name in the field of radar technology, applying his work to the war effort in the UK at the Telecommunications Research Establishment at Great Malvern, where he studied V1 and V2 rocket defences. A curious aside is that the secret radar system he developed for the British also gave rise to one of the most famous and successful wartime disinformation campaigns ever: that eating carrots helped allied forces see in the dark (and not any new technology based on sensors or radar).

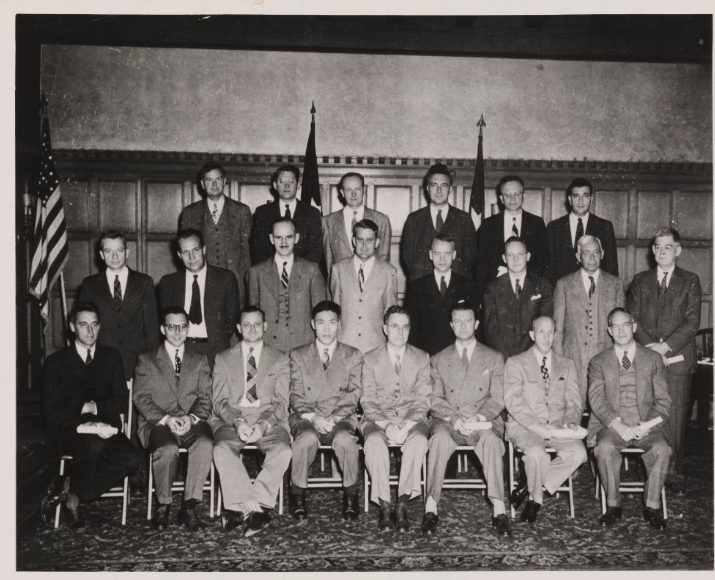

Trump’s work was commendable enough to earn him direct recognition by both the UK government (he received the King’s Medal for service in the cause of freedom) and the US government (receiving the Certificate of Merit, awarded to him by Harry Truman). Below is a picture from the MIT Museum cataloguing the award ceremony:

Safe in the knowledge that Tesla’s belongings were unlikely to be weaponised, the Office of Alien Property eventually decided to release the property to a distant relative of the inventor. He, allegedly, took them back to the eastern bloc.

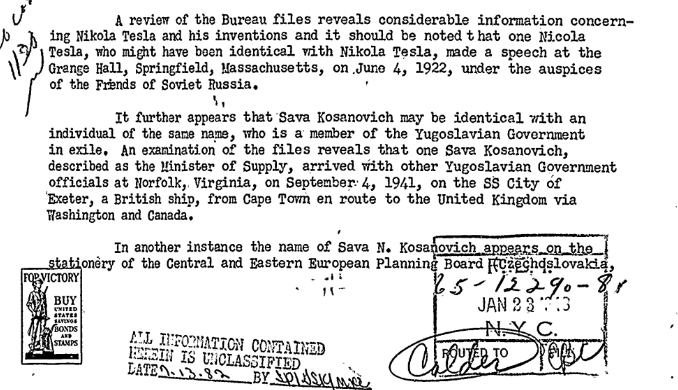

But not everything was necessarily as it seemed. The declassified files also show that at least one special agent remarked that the relative in question, Sava Kosanovich, did not appear to be very well-liked by Tesla:

Letters signed by J. Edgar Hoover, meanwhile, revealed concerns about both the inventor’s and Sava Kosanovich’s potential communist leanings. The latter, it was noted, had appeared on the stationery of the Central and Eastern European Planning Board for Czechoslovakia, Greece, Poland and Yugoslavia, where he was described as operating as chairman of the board and minister of state for Yugoslavia. The documents also reference that Tesla’s rent at the New Yorker hotel may have been paid by the Yugoslavian or Czechoslovakian governments directly for years.

As fascinating as all this is, however, it’s only a side story. Because this isn’t just a tale about missing Tesla papers or secret death ray weapons. It’s also the story of the postwar communist roots of the Tesla brand itself.

Little did Tesla know – or perhaps, being a futurist, he did – that, by the 21st century, it wouldn’t just be his works that would become household names and hotly contested assets in their own right, but also his name. And that’s not just because his name has become synonymous with electric vehicles thanks to Elon Musk.

It’s because of the much stranger story of a state-run entity in former communist Czechoslovakia, which bagged the rights to Tesla’s name long before Elon Musk was even born. But also how it still benefits from the trademark to this day.

What’s in a name?

You wouldn’t think that intellectual property and communism go together. But as the 2023 Apple TV film Tetris has highlighted, nothing could be further from the truth.

For those who haven’t seen it, Tetris tells the story of the last-minute scramble by Nintendo just as the USSR was breaking down to secure the global distribution rights to the blockbuster computer game Tetris so that it could be bundled into their Gameboy handheld console package at launch.

The game itself was invented by Alexey Pajitnov while working at the Computer Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences with the help of a teenager called Vadim Gerasimov.

Gerasimov later recounted on his personal website the oddness of doing business during that transient twilight period when the USSR’s historic non recognition of intellectual property rights was suddenly and abruptly beginning to thaw.

In the Soviet Union, where private business was outlawed and the concept of intellectual property was not defined, people could not make private business arrangements of this kind. The Computer Center of Academy of Sciences owned everything we made. Several years later the situation in the Soviet Union changed, but this was a different story. When I worked on Tetris, even a government organization could not formally hire me because I was underage. I worked on Tetris just for fun. I don’t remember Pajitnov ever paying me for anything related to Tetris either. Pajitnov started fixing the business aspects of the situation a few years later when he and Henk Rogers participated in negotiations with Elorg (the only government organization in the USSR that could sell software abroad). Pajitnov stopped by my home and asked me to urgently sign a paper “to get lots of money for us from game companies”.

He didn’t leave me a copy of the paper. As far as I remember the paper was saying that I agree to only claim porting Tetris to the PC, agree to give Pajitnov the right to handle all business arrangements, and refuse any rewards related to Tetris. I did not entirely agree with the content, but I trusted Alexey and signed the paper anyway. In a few months my name disappeared from all newly released versions of Tetris and all Tetris-related documents. Alexey registered a US copyright (R/N PA-412-170) referencing the free PC version of Tetris (original version 3.12) we developed together.

The organisation in charge of importing and exporting computer technology in and out of the USSR was Elorg. And, as the Apple TV film beautifully illustrates, anyone wanting to extract valuable commercial properties out of the crumbling bloc at the time, had to seize the moment. The USSR was chock-full of massively undervalued assets that could be commercialised at huge profit abroad, but only if the right people could be persuaded to sign off on materials during a fleeting moment of opportunity.

For more on how the scramble for Tetris helped to bring down Mirrorsoft group boss Robert Maxwell, go see the film.

But the USSR, obviously, was not the only one that relied on similar structures. Most Eastern bloc countries had similar state-run enterprises and monopoly controlled import-export agencies. Czechoslovakia was one of them.

How the Czechs bagged Tesla

Speak to any middle-aged Czech or Slovakian and ask them about Tesla and chances are it’s not electric cars or Elon’s futuristic Tesla logo that springs to mind, but rather the far more elegant and iconic styling of the company that bore the same name but made almost all of Czechoslovakia’s essential electronics, computers and appliances.

It too depended on its own version of Elorg, the import-export agency known as Kovo. “Kovo was a gateway to abroad,” as I was told by those in the know. It was only through Kovo that Tesla goods could be marketed abroad at international trade fairs and such the like. For a flavour of the operation head to Ebay, which is jam-packed with purpose-made Tesla marketing and promotional material for such shows (not least because so many of the designs are authentically beautiful and collectible):

It too depended on its own version of Elorg, the import-export agency known as Kovo. “Kovo was a gateway to abroad,” as I was told by those in the know. It was only through Kovo that Tesla goods could be marketed abroad at international trade fairs and such the like. For a flavour of the operation head to Ebay, which is jam-packed with purpose-made Tesla marketing and promotional material for such shows (not least because so many of the designs are authentically beautiful and collectible):

But what exactly was Tesla?

The true origins of the Tesla company go back to 1921, when the company was known as Elektra. The company was later bought by Philips in 1936, and operated as such until the end of the Second World War when eventually it was acquired by the government and nationalised. By March 1946, it had been decided the company would be renamed Tesla as a tribute to Nikola Tesla who had died just three years earlier. According to Wikipedia, the rebranding ceremony took place at the Mikrofon Factory in Strašnice and was attended by government ministers from Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Macedonia, a clear nod to the inventor’s heritage since he had been born in a small town in what is now modern-day Croatia.

But the heartfelt feelings for Tesla weren’t to last. When the USSR officially broke off relations with Yugoslavia in 1948, the Nikola Tesla connection was deemed a little too awkward and thus inconvenient. The official line soon became that Tesla was actually an abbreviation for TEchnika SLAboproudá, which means “low-current technology”.

Strange recollections

As a UK-born Pole born in the 70s, I happened to be in and out of communist Poland frequently as a child. I was no doubt exposed to all sorts of communist-bloc brands and organisations on a subconscious level. But it wasn’t until my father made a flippant comment about how the plotline of Tetris reminded him of Kovo and Tesla that I consciously registered that that niggling feeling I’d always felt about Elon Musk’s Tesla — that somehow I knew I had seen that brand name before — had not been wrong.

There was another Tesla. And its brand imagery had made more than a firm imprint on some part of my brain, even if it had been egregiously written over by the new Tesla many decades later. Either way, the images of the original Tesla branding I found on the internet spoke to me on a visceral level. Memories of old radios, tape recorders and other electricals filled my head.

Here’s a very small flavour of the Tesla appliances and electrical devices that might have popped up in any communist household in the 80s.

Radios …

Calculators …

Clocks …

Computers …

Note the stylised simplicity and beauty of the logo.

But there was so much more. Television sets, radio receivers, transistors, integrated circuits, speakers, gramophones, cassette recorders, CD players and even fancy nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometers. Tesla also became one of the biggest distributors of electronics to the communist bloc and an active installer of radio and television transmitters in most of those regions.

To really get to the bottom of the story, I soon realised Googling about Tesla’s current state was not going to be enough. The more I researched online, the more confused I became. There were a plethora of different Tesla outfits in the Czech Republic, all with different websites, corporate identities and more often than not different logo styles too. There were all sorts of derivative groups of Kovo too.

It was clear I wasn’t going to get any clarity from London. I needed expert help.

And then, as if by magic, an amazing opportunity presented itself. Entirely unrelated I was invited to attend a CBDC conference in Prague. This, I thought to myself, was my unbelievable chance to get close to some Czechs who might actually be in the know about such matters.

The conference did not disappoint.

Upon arrival, it only took a few inquiries before my well-connected hosts introduced me to the softly-spoken Petr Matejcek, a partner at the organisation that today controls the Tesla trademark. This is Matejcek below:

We sat down for a coffee and he graciously told me everything I wanted to know — from Czech Tesla’s history and its command over the Tesla brand to its current payment ambitions and ongoing relationship with Elon Musk.

Matejcek himself is best described as old-time Tesla acolyte. While he never worked directly for the company during the communist period, he told me his uncle had installed large radio and TV transmitters for Tesla in far-flung places like Beijing over the course of the 1960s.

“It actually changed my life because he was outside working in China and it directed me to foreign trade,” Matejcek said, explaining that his parents, who were very much against the communist regime, had blocked him from working in the trade sector he had set his heart on until the end of the 1980s. “It was always my dream to work in this branch.”

By the 80s, Tesla was a very big company. The company had more than 100,000 employees with 50 different companies that exported to more than 140 countries. Its development had accelerated over the course of the 70s when many different manufacturers, production companies and trading companies were established, making everything from small electronic spare parts to auto industry components, TV industry recorders and transmitters.

But then communism fell. And everything changed. For Tesla the dawn of the capitalist era mostly meant fragmentation. As Matejcek explained, thanks to the country’s privatisation voucher system, Tesla’s various divisions fell into the hands of many different private owners. All of them now had to go it alone.

“It was very tough for Tesla,” he said “Because from one day to another Tesla lost the markets to Eastern Europe and the Comecon countries, as well as Asia, China, Indonesia, Philippines and Vietnam.” Many of the companies couldn’t cope. Their lower-quality products couldn’t compete easily in an open and competitive global market marketplace meaning soon enough most of them failed.

The beating heart of Tesla nevertheless continued on. At least for a little longer. It was called Tesla Holding and it alone owned the name, history and logo of the entire Tesla complex. (It’s this logo which is proudly positioned on Matejcek’s business card.)

But. it too eventually fell upon hard times in 2007, and became subject to a takeover by Irish entrepreneur Enda O’Coineen and his Kilcullen Kapital Partners vehicle. They, stupidly — at least to Matejcek’s mind — changed the logo “to a very ugly one” and were no more successful as a result. By 2010, an opportunity once again arose for a small group of old shareholders, mostly former employees, to pay off the debt incurred and repurchase the company. Tesla Holding’s current corporate structure was born from that moment. Today it is headed by Frantisek Hala, one of the company’s oldest employees.

“He’s 75 years old but he started there when he was 16, or something like that,” Matejcek said.

As Hala told Czech Radio in 2022 about the history of firm:

“We were given the task to develop a television transmitter which we did and, in 1953, the broadcasting was successfully launched from a transmitter we installed in Petrin. This started a golden era for Tesla when we produced TV and radio transmitters and TV sets and radios both for Czechoslovakia and for export. And we established close cooperation with the army which has always relied on Tesla for its communication technology.”

In its heyday Czech Tesla had facilities and factories all over Czechoslovakia. One of its most notable sites was in Pardubice, about 70km from Prague. Today, this has been fittingly repurposed into the Czech base of Foxconn, counting as one of the group’s biggest facilities in Europe.

Other former Tesla factory sites, however, haven’t been as lucky. The site at Hloubetin is currently being developed into a residential block:

But it is through Tesla Holding, which owns the legal right to the name, that the brand continues to proliferate worldwide.

Matejcek told me that, even today, there are scores of companies operating in many different fields under the Tesla name, all licensed through agreements with the his parent holding company. “For example, Tesla Smart is a company founded four or five years ago, and they are allowed to use the name Tesla Smart,” Matejcek said. Another, he said, is Tesla Lightning, which manufactures lightbulbs which are produced in China.

Even the old manufacturers, he said, had to get new licences from Tesla Holding and continue to pay annual fees for a right to use the name. Though, technically, he added, anyone can apply to Tesla Holding for a right to use the name in a specific jurisdiction and for a specific service. And many international licencees have been granted. Over in the US, for example, chipmaker Nvidia has the right to make Tesla-branded chips, and pays Tesla Holding for those rights annually.

From Elorg to Elon

So what about Tesla Motors? I simply had to know.

“There is a very funny story,” Matejcek said. “Around 2008, the [Czech] Tesla lawyer found out that there was a guy in the United States running around the US and using the name Tesla. They approached him and they told him, ‘Look, it’s illegal to use the name Tesla”.

This, it turns out, was Elon Musk and Tesla Motors. According to Matejcek, the two groups negotiated for nearly two years until finally, in October 2010, they signed the agreement that governs today’s trading relationship.

“By this agreement, Tesla Motors got the legal right to use the name Tesla but only for cars, different spare parts of cars and for batteries for cars,” Matejcek explained. “And only in the United States, the European Union, Russia, Turkey, Switzerland — and I think that’s it. It was focused.”

To maintain the rights, Tesla Motors must pay the agreed-upon set fee “for eternity”. While Matejcek wouldn’t disclose the exact sum agreed upon because of confidentiality agreements, he said it was worth bearing in mind that back in 2008, when negotiations started, Tesla Motors was hardly known anywhere. This would have affected the price.

The problem, Matejcek noted, is that eventually, Tesla Motors wanted to spread its activities to different countries beyond their agreement, such as China. For the most part, Tesla Holding was fine with the expansion. Matejcek said the company didn’t want to pursue the trademark violation in court (no doubt because doing so in China is no easy thing). But, he added, there was now a complexity because of a case in Australia involving battery rights, which he didn’t expand on.

Matejcek himself bought the licences for Tesla Smart Technologies and Tesla Smart House in 2016 with a view to selling Tesla solar and smart home branded products. He said he was now working with partners in the Philippines and Indonesia on efforts to launch the business there. “This partner of mine [in the Philippines] has a satellite covering the Philippines with internet signal. And we would like to call it Tesla,” he said, adding that the project was endorsed by the government because it aimed to digitalise the whole country. The venture is, somewhat ironically, set to bounce signals off Starlink satellites, too.

In another play on the brand name, Matejcek has also bought the rights to ‘Tesla Pay’. Originally, his objective was to use the brand name to launch a payment system that would allow Chinese tourists to pay in Czech shops, restaurants and hotels with WeChat pay and Alipay. But things didn’t go quite as planned.

“We developed the internet platform, under the brand Tesla Pay and everything was done, everything was prepared,” he said, explaining he’d got the idea from SendyPay in Moscow which facilitated payments for Chinese tourists there. But then Covid struck, and the Czech Republic stopped all the flights from China. “It was a disaster for us,” Matejcek said.

“We invested a lot of money and signed an agreement with a Taiwanese partner in March 2020 to make it happen.”

Where there’s a will there’s a way

But Matejcek hasn’t given up on Tesla Pay just yet. He said he’s now working with another partner to launch a similar Tesla Pay payment system in the Philippines. I couldn’t help but note the degree to which his operations echoed those of Elon Musk, given his PayPal roots and alleged Twitter X payment aspirations. But turns out Matejcek was well ahead on this relationship, too. “Peter Thiel, yeah, I met him several times,” he said, albeit in connection to a solar business he had run in California in 2003.

But how did Matejcek really feel about Elon, given the similarities of their businesses?

At first, it seems, he didn’t like him at all. “I was jealous that he used this Tesla [name],” he told me. “But then, with his space programmes, I changed my mind. When I saw SpaceX, I put my head down and thought to myself he was a good guy because SpaceX, it’s an amazing project.”

Overall, Matejcek said, he believed Musk had done a great job for the Tesla brand and allowed it — as well as the memory of Nikola Tesla — to gain new resonance with another generation. He would love it, he said, if Musk would one day come to Prague. “We’ve invited him to Prague many times but he’s never come.”

Not coming would be a shame. It’s a strange coincidence, after all, that the original Tesla logo — with its undulating curve and star, evoking space time — embodies the spirit of Elon’s portfolio companies as much as it does the post-war aspirations of a state enterprise that specialised in the manufacture of electrical devices in former communist Czechoslovakia.

It’s almost like the two are one and the same.

And that’s without even mentioning the original Tesla divisions that operated (and in some cases still do, or at least did until losing their security clearance very recently) for the defence department and the military.

But if we’re going to go there, the most famous of these military divisions was found at the Pardubice Tesla plant, which in 1981 began the development of ‘Tamara’, a sophisticated radar system, allegedly the only one in the world capable of detecting stealth military aircraft. What’s notable too, according to Wikipedia, is that after communism fell, Tesla’s lead radar engineers formed the ERA company, which is still situated in Pardubice to this day. This now produces the VERA detection system, a technology which supposedly gives NATO “an edge when it comes to detecting aerial and naval threats”, especially from Russia’s powerful electronic warfare capabilities.

According to an article in C4ISRNET in 2018:

Today, Era is supplying at least 20 nations with passive miltiary surveillance sensors and it supplies the NATO alliance for its deployable air command and control system.

It’s also being actively provided to the Ukrainian war effort today.

Which is, of course, another funny coincidence and a nice way to loop back to John G. Trump’s work on radar during WW2. (Without even having to tie anything to Czechoslovakian born Ivana Trump or the brand genius of Donald J Trump himself, a man who definitely knows the value of a franchise.)

As to who exactly was behind Tesla’s iconic and mesmerising logo? We might never know. Matejcek offered no clues other than that he knew it went back as far as the 1950s.

What’s certain is that its most beautiful and observable depiction is found in a stained glass rendering in an old communist passage near Prague’s famous Wenceslas Square.

If you ever get a chance to visit Prague, do head over to Světozor passage to take a look yourself … (but don’t be surprised if someone relatively mysterious hands you some microfilm or an encrypted message while you’re down there).

Further reading:

Home computers behind the iron curtain – Hackaday

An army contractor from an opaque group lost its clearance – Seznam Zpravy

Memories of NMR in Brno Tesla – Vladimir Zeman

One Response